Constança Arouca | Madalena Parreira

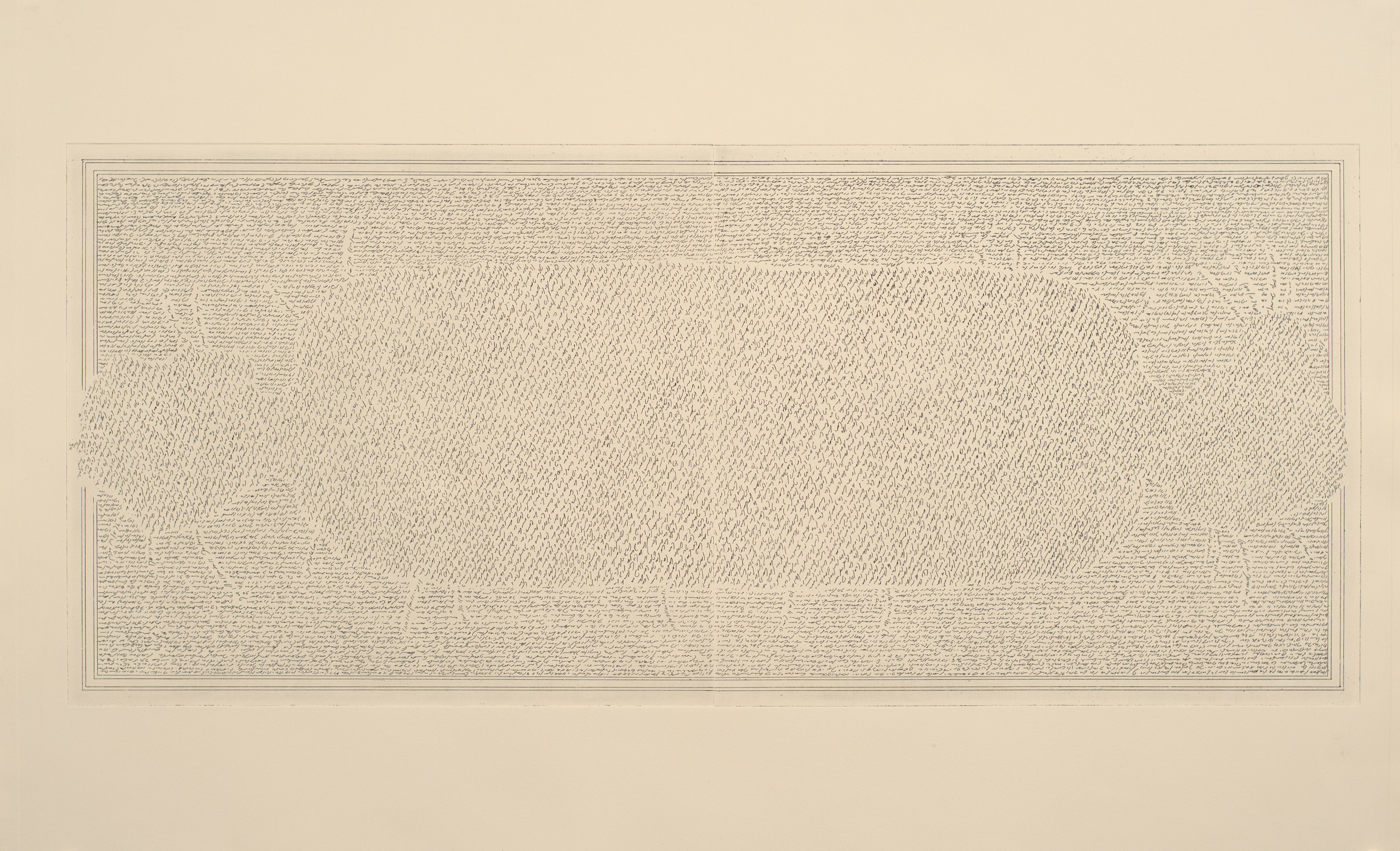

Maps 12 & 15 von Willebrand Collection Vault map (12) and inset (15)

(Dresden, Germany, 1919?) *see introduction

Cartographic Treasures of the von Willebrand Collection

Following the outcome of the Berlin Conference, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck perceived a pressing need for a systematic sweep of cartographic archives to identify opportunities to fulfill German territorial ambitions - as well as documentation to refute spurious claims from the other Great Powers during the Scramble for Africa. The Iron Chancellor assigned a portion of this effort to his third cousin, Albrecht Ulrich Phillip Hartmut von Willebrand. Historians still speculate why the able statesman would commission anything from the notoriously incompetent von Willebrand, who insisted on being addressed as the Margrave of Hohnburg, even though the title had officially been declared extinct since the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. Part of the answer surely lies in the specific task assigned to the Margrave: “to collect copies of all cartographic materials of apparent irrelevance to current territorial disputes”. In keeping with this, an entry in the diary of Graf von Moltke (the Elder) has the Chancellor remarking “let us inflict this buffoon on provincial librarians while we get on with the affairs of state.”

Oblivious to Bismarck’s motives, the Margrave threw himself into the task body and soul, ultimately accumulating over sixteen thousand maps, charts, and an assortment of unclassifiable prints which he believed “might one day show someone the way to something or somewhere.” In keeping with the original commission, a notable aspect of the von Willebrand collection was its total uselessness during the continental upheavals between 1875 and 1945.

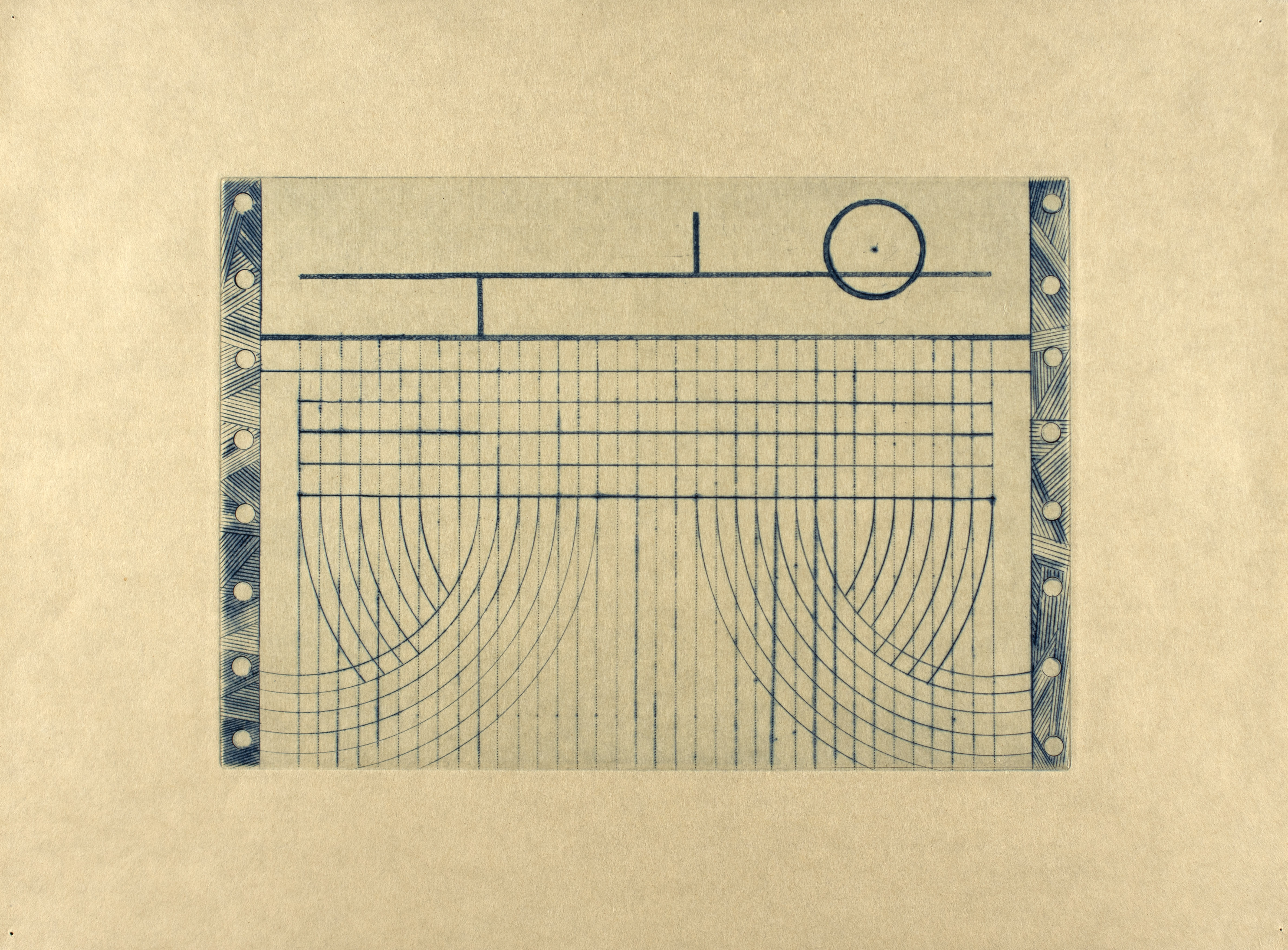

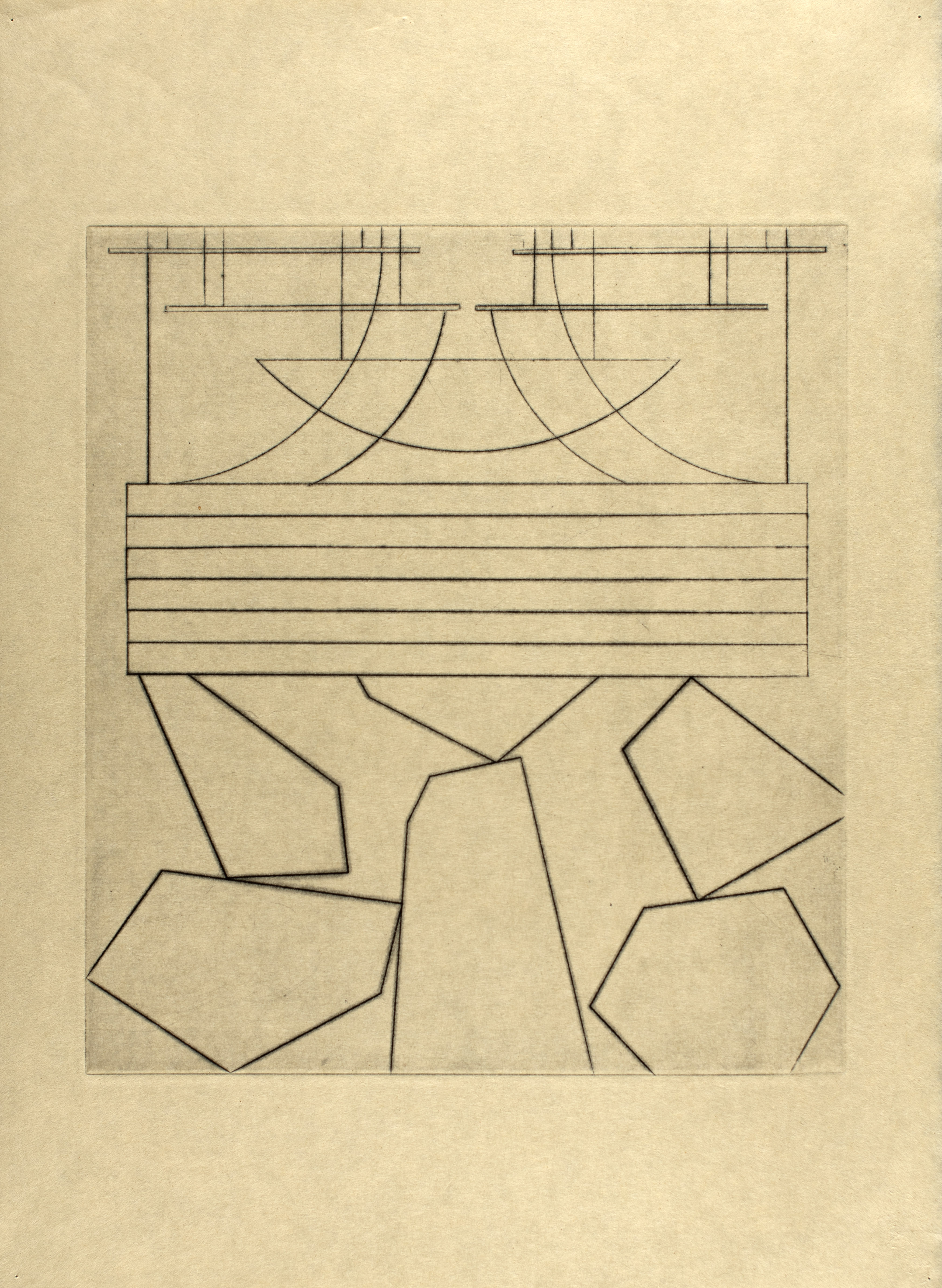

The collection was housed in the von Willebrand family annex to the cloisters of Dresden’s Sophienkirche until the aging Margrave panicked at what he considered to be the imminent collapse of the Siegfriedstellung (Hindenburg Line) in 1915. Still under the illusion that his collection would one day prove vital to German strategic interests, von Willebrand ordered an underground vault to be constructed for its concealment. After the Treaty of Versailles, the Margrave, ever the visionary, believed that Europe had had enough bloodshed and considered his mission concluded. Desperate to be fashionable, the Margrave took a decision that would have dire consequences for the collection: he commissioned an engraved map of the von Willebrand collection vault in a mishmash of contemporary styles, vaguely inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s plans for the Imperial Hotel (Map 12-15).

von Willebrand lived to the age of 97, finally expiring at a spa outside of Kaiserslautern, an obscure minor nobleman who never escaped his internal exile to the provinces. He died in the same year as the Weimar Republic, in 1933. The Margrave’s ill-advised attempt to keep up with the times led to the von Willebrand vault map’s misidentification as Degenerate Art. As a result, almost all copies were destroyed by the newly established Reich Chamber of Culture. Only the original copper plate matrix of the vault map remained untouched in the Sophienkirche annex, together with a pair of printed copies. The church was comprehensively destroyed during the Allied bombing of Dresden in 1945. Incredibly, a controlled detonation of unexploded ordinance in the immediate postwar period led to the unearthing of the vault map plate and a pair of prints in pristine condition, one of which you see here in this exhibition.

The von Willebrand vault map came to the attention of Arthur Robinson, the Office of Strategic Services’ cartographic wunderkind, who was able to locate the trove and transported all sixteen thousand maps (miraculously, all the works on paper had survived the Dresden firestorm) to the headquarters of547th Engineer Construction Battalion,garrisoned atGelnhausen Kaserne. Robinson invested considerable energy to rescue the maps from the rapidly advancing Soviet Army. Robinson had believed the collection to be of strategic value, and for years lamented endangering his men to “recover some dilettante’s glorified stamp collection”.

The von Willebrand collection returned to Dresden three years after the collapse of the DDR. It is currently housed in a custom-built facility near its originalSophienkirche location. Almost all the works, spanning four centuries, are prints. A unique feature of the collection was its matched sets of prints and copper plates. Copper, however, was a precious commodity in postwar Germany, and scavengers made off with all but one of the plates.

The maps are made available to scholars by appointment, and von Willebrand residencies in Dresden are highly coveted by cartographers, but this exhibition marks the first loan of maps from the von Willebrand Collection.

Prof. Horst Manfredsenjense, Ph.D.

Head of Collections, von Willebrand Trust

Works:

This Renaissance print is a copy of a vellum drawn circa 1156 at the behest of Conan IV (“the Black”), Duke of Brittany, during a dynastic dispute with King Henry II of England, who was also Count of neighboring Anjou. As shown in the inset, the image’s purpose is solely to assert power and legitimacy. The multiple lines shown in the inset (the only remaining panel of a set of three) proclaim the conquest and rule of the corresponding regions by the Duke and his kinsmen in the House of Penthièvre.

This map is part of a series commissioned by King James VI during his attempt to pacify the “most barbarous Isle of Lewis”. It is of little strategic interest, as it charts two nearby uninhabited islets of no economic significance, but it has one unique feature: the engraver was clearly working

from a palimpsest in vellum and decided to copy into the plate the still legible underlying text – a text which has absolutely no connection to the region depicted (it appears to be a list of penances compiled by the Observant Franciscan Friars of Aberdeen).

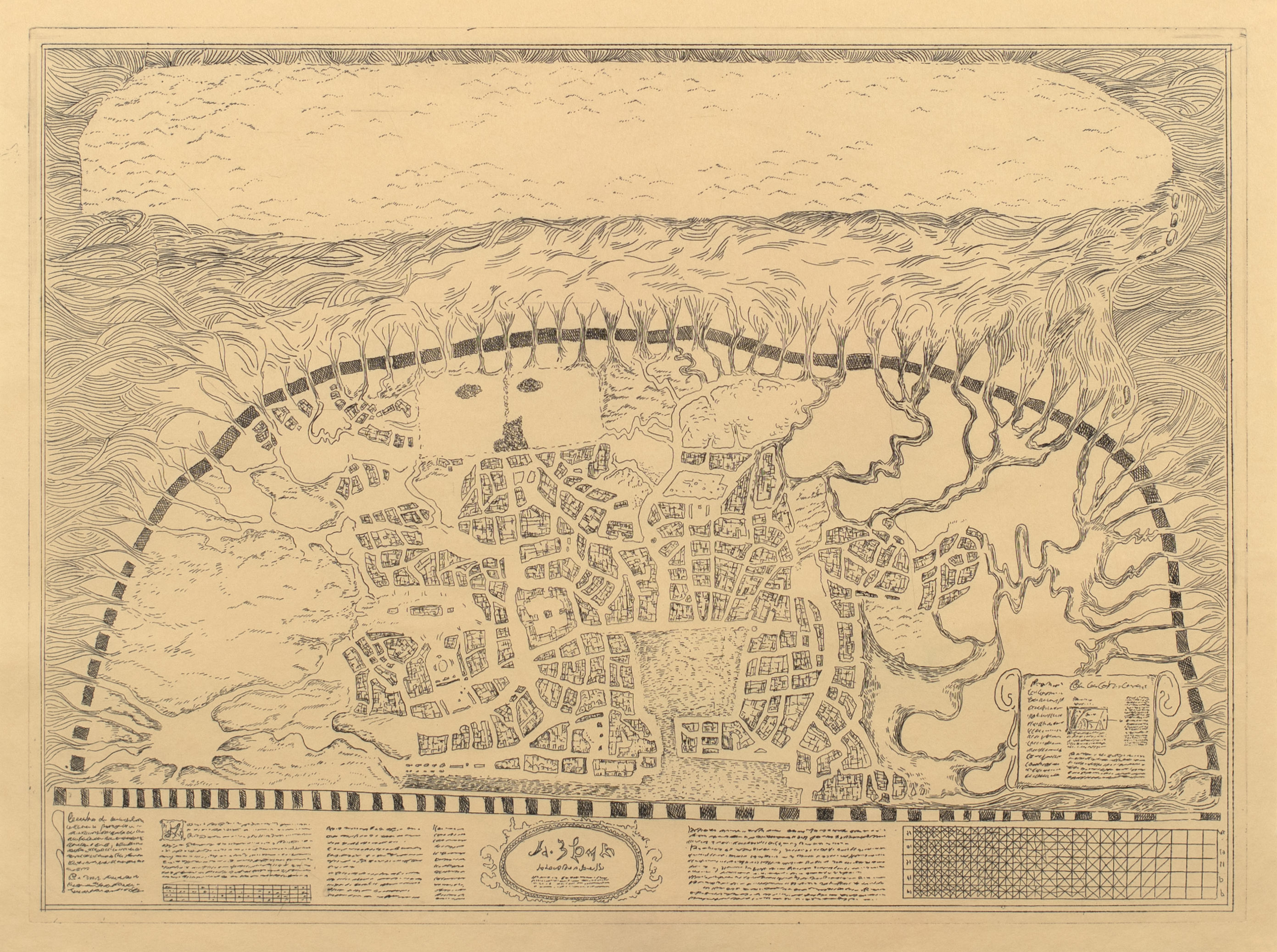

Another mysterious map in the von Willebrand Collection. The name refers only to where the print and (lost) plate were purchased from a dealer who provided no information on provenance. This may be the most familiar map in the collection, adorning countless t-shirts, posters, and for some inexplicable reason, two of the five most popular Romanian beer labels. The Nuremberg Enigma’s notoriety does not primarily derive from the unidentified town it depicts, but rather from the undecipherable script which appears to bear no relation to any known linguistic system – unlike Linear A, linguists cannot even identify the signs for numbers.

Map 5 Untitled fragment (Unknown)

This print has baffled scholars for over a century. No provenance information exists for it, nor any form of accompanying notes or documentation. It is still debated whether it is a map, chart, or even perhaps a part of an anatomical drawing or technical blueprint. Most experts agree that it is part of a larger, multi-panel image, but no other panel has been identified.

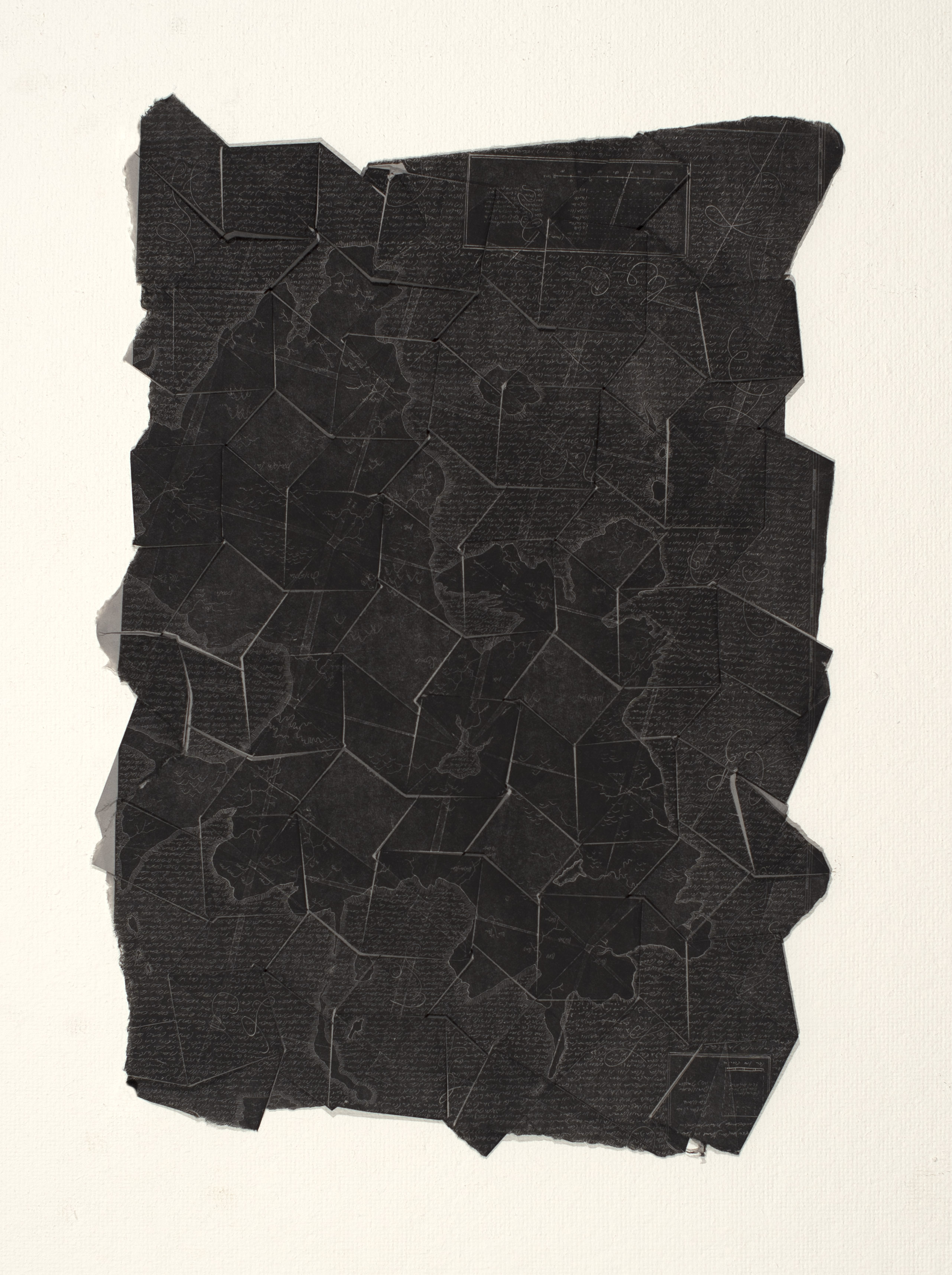

Maps 6 & 9. The Origami Maps (Dresden, 1914-1918)

These maps, or objects, represent the sole known instance of an attempt at creativity by the Margrave. Like so many Europeans of his generation, von Willebrand was enthralled by Japanese art, and he developed a particular fascination with origami – a set of techniques with ancestral origins in Japan whose basic principles influenced the “folds of truth, folds of life and folds of beauty” ideas of German pedagogue Friedrich Fröbel.

Tragically, von Willebrand brought his newfound creativity to bear on the problems of cryptography – the Margrave was ever mindful of his duty to the Fatherland. von Willebrand’s work on the tactical applications of origami in the battlefield somehow managed to pique the interest of the Kaiser’s father, Frederick III, during his brief 99-day reign. When Frederick died, his relationship with the Margrave ultimately led his son Kaiser Wilhelm II to authorize a field test of the origami system during the Third Battle of Ypres. As a result, an entire German reconnaissance platoon was picked off one by one by a perplexed British sniper as they tried to fold paper while wearing full anti-gas gear.

Map 7 & 8. The la Motte-Husson Portolan (Mayenne, France, 17th Century)

If, as Arthur Robinson wrote in his Elements of Cartography, “maps are to be looked at while charts are to be worked on”, then portolans are the quintessential charts, navigational guides that do not wrestle with other aspects of representation. The Margrave was ecstatic when he acquired the la Motte-Husson Portolan, believing that it would finally allow him to contribute to the defense of the nation. Over time a confusing series representing the same location emerged, with shifting sailing directions. Exhaustive archival investigation revealed that the Baglion de la Dufferie family had the series of prints made to mark the different routes used by the toy sailboats of the Dauphin (the future Louis XIII) to cross the moat of their home in Mayenne, the Chateau de la Motte-Husson. This discovery made thirty years after the series was acquired precipitated a severe depression – it was the reason von Willebrand chose to recuperate in the Kaiserslautern spa where he ultimately expired.

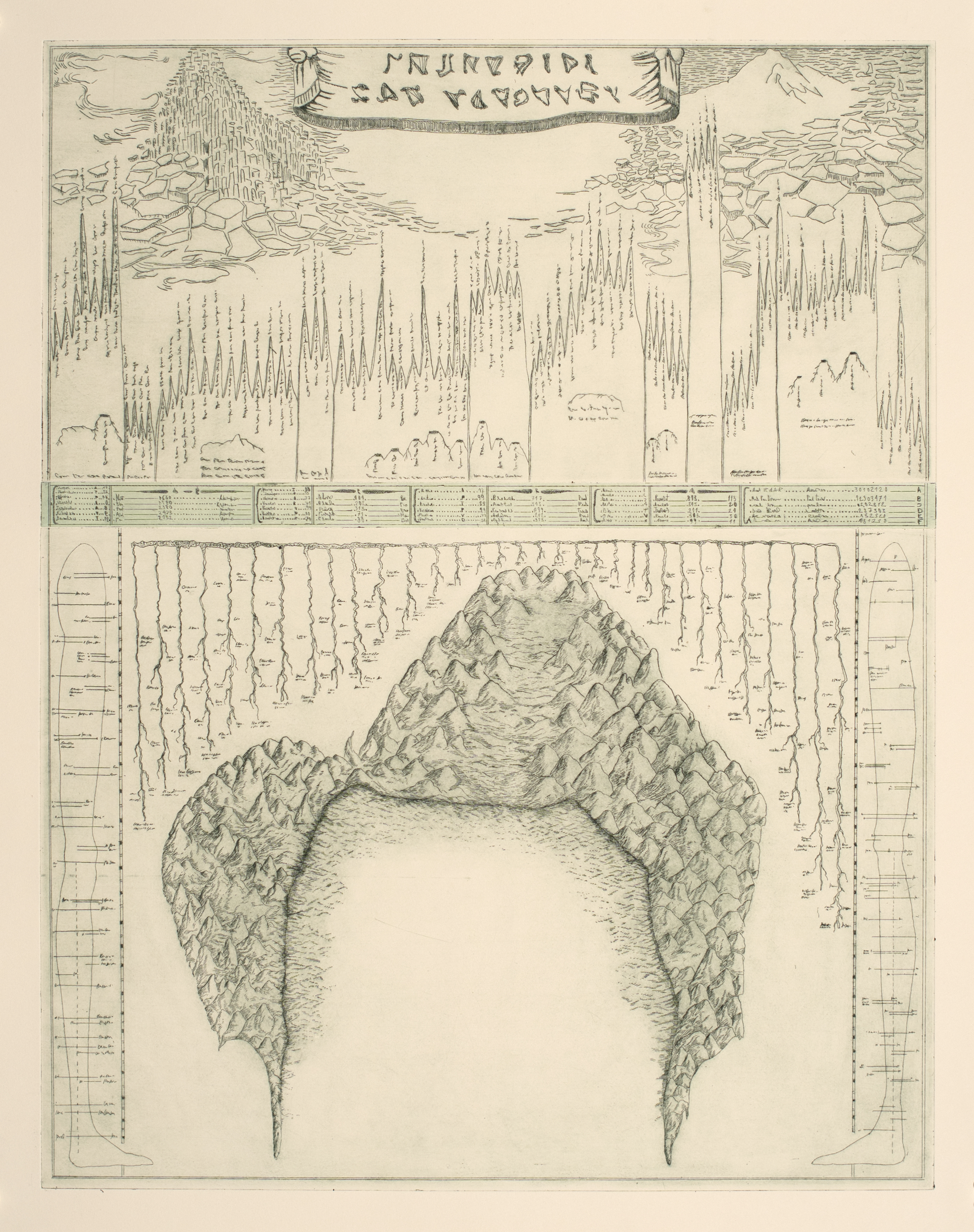

Map 10 The Turbulence Chart (Lviv, Ukraine, circa 1890)

This engraving was part of a set that illustrated the fabled, never published, “Order & Disorder” manuscript by Bronislaw Zamoyski (sometimes referred to as the “Leibniz of Lviv”). The text and all accompanying illustrations were thought to have been lost when the Russian Army captured Lviv in 1914. How it was obtained by von Willebrand remains unknown.

Scholars speculate that finding this image was the true objective of Robinson’s OSS unit, on the direct orders of General Leslie Groves. Zamoyski’s biographer, Jan Wajda, claims that oblique references to it exist in the declassified Venona transcripts – references which would indicate that the Soviets were also searching for the Turbulence Map. Unfortunately, the relevant sections are heavily redacted. The Turbulence Map is a perennial favorite of cartographic conspiracy theorists, who like to point out that as the DDR fell, a lieutenant colonel in the KGB named Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin was in Dresden, diligently burning documents until the

last possible minute. In a bizarre twist, we know that this print is a later copy, if not an outright forgery – microscopic plastic shards unambiguously establish that it was printed from an acrylic plate.

The print was examined at length by Benoit Mandelbrot in 1993 when the von Willebrand Trust made the collection available to scholars. Mandelbrot never published a single word on Zamoyski’s work, but one of the archivists has stated that he saw the great man quietly weeping as he handled it.

Map 11 The Two Ladies (Leiden, Netherlands, circa 1790)

The Two Ladies is a direct reaction to the vision of medicine put forward by the Encyclopedists, particularly in d’Alambert’s treatise on the primacy of sensory knowledge and experimentation, the Discours préliminaire. The two female figures are a not-even-thinly veiled insult directed at Diderot & d’Alambert (it was a time of rampant misogyny and Dutch humor remains to this day, as they say, no laughing matter). The image is not a map but rather a chart of sorts, with texts of Galen’s prescribed treatments overlaid on the corresponding afflicted body parts. The Margrave brought a copy of this print with him to Kaiserslautern in 1933, but it is not known if Galen’s typology of human temperament played any part in von Willebrand’s course of treatment.

Map 13 La Signora di Piombino (Florence, Italy, 1655)

Being fleeced by unscrupulous dealers hawking Leonardo Da Vinci “masterpieces” is a rite of passage for wealthy collectors, and the Margrave was no exception. This work was sold as a contemporary reproduction of a vellum map concealed in the lining of a lady’s dress supposedly drawn up by Leonardo while in the service of Cesare Borgia. It represents the freshwater sources near the Tuscan coastal town of Piombino, conquered after a prolonged siege by the fearsome condottiero in 1502. Though the original map was indeed produced while Leonardo was in Piombino, he did not make it

– furthermore, it has since been established that this print was produced in Florence, over a century and a half later.

Map 14 The Fluvial Print (Caldas da Rainha, Portugal, 1855)

The Fluvial Print’s provenance is well-established, but the region represented in the map has never been determined. In 1972, Portuguese geographer Nuno Nunes Machado was widely ridiculed at the IV International Cartographic Association meeting in Ottawa for proposing that the print was nothing more than the Tagus River margins, in an inverted orientation. Cutting-edge research using Artificial Intelligence to exhaustively scan satellite images may give the Portuguese scholar the last laugh.

16, 17, 18 Custom printed telegrams used to request prints and copies by the von Willebrand collection archivists

(Dresden, 1900-1915)

The exhibition “SPAM” was presented at Rua da Bempostinha 64C, Lisbon in November 2021.

With special thanks to:

Alessandra Baroni Alexandre Camarão

Ana Dias

Ana B Martinho António Marques

Ana Santos

Bernardo Simões Correia Carolina Carvalho Catarina Marto Constança Arouca Fernanda Carvalho Fernando Cwillich Francisca Carvalho Francisco Fonseca Guida Casella

Hugo Amorim

Isabel Aguiar/Vitor Millheirão Isabel Zarazúa

Joana Reis

Joana Solipa Batista

João Jacinto

João Miguéis

Institutional Funding and support:

Jorge Nesbitt

Juliana Campos Leonor Parreira Madalena Parreira Maria Ana Vasco Costa Maria Mire

Manuel Caldeira Manuel Castro Caldas Marcelo Costa

Maria João Brito Mariana Cardoso Miguel Branco

Nádia Neves

Nuno Crato

Pedro Proença

Pedro Tropa

Ricardo Fonseca Sally Baker

Sandrine Llouquet Thiago Carvalho Tiago Albuquerque

República Portuguesa e Cultura

Ar.Co – Centro de Arte e Comunicação Visual